From Hypertext to Hypermedia - I

The origins of the modern web, quirky dead-ends, vaporware, and everything in between...

Rumblings of the Internet

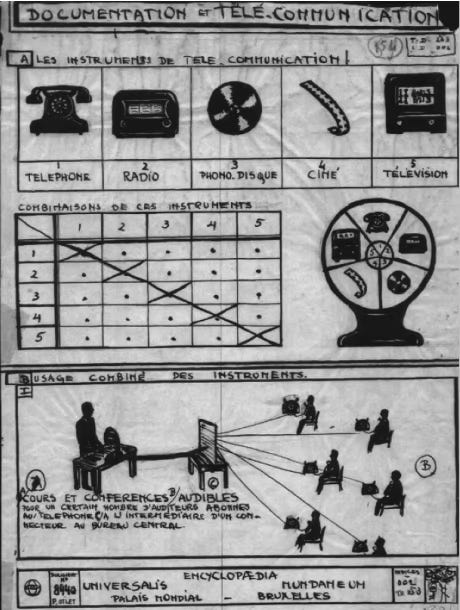

A thinker seldom talked about these days is Paul Otlet, which is very odd since he first pioneered the idea of a search engine (and implemented it with paper!) and innovated a knowledge organization system (Universal Decimal Classification) that is used to classify knowledge to this day. His Mundaneum was in effect a paper version of today’s Wikipedia, albeit far more centralized.

But what is more relevant to the discussion is his work on what is known today as hypertext.

An examination of the ideas and procedures that governed their (Palais Mondial/ Mundaneum’s) development suggests how similar what was intended was to hypertext systems. The repertories or databases consisted of nodes or chunks organized by a system of links and navigational devices that allowed the movement of the user from bibliographic reference to full text to image and object.

The monographic principle applied to standardized cards and sheets represented one of the two major components of modern hypertext systems-nodes. The other, links and navigational systems, is reflected in the transformation by Otlet and his colleagues of Melvil Dewey’s Decimal Classification system into the Universal Decimal Classification system. This was to become what Carlson (1989) has identified as one of the essential components of a hypertext information storage and retrieval system-“an assistance processor: a retrieval mechanism (or collection of retrieval mechanisms) for effective access to and management of the database” (p. 62-63).

From Visions of Xanadu Paul Otlet (1868-1944) and Hypertext

A similar experiment to the Mundaneum, called the Bridge, was run by William Ostwald in Germany, who was inspired by Otlet’s work (this later collapsed due to lack of funds)

What is remarkable about Otlet’s vision is that his version of hypertext included support for “online” access. The thinkers after him, the ones usually credited with the invention of hypertext as a concept, would not be so insightful.

Proto-Hypertext

Most major histories of hypertext begin with Vannevar Bush’s essay “As We May Think” in The Atlantic Monthly, published in July, 1945.

In the essay, he describes his idea for a device he called the “Memex”, a “private file and library”. He envisions this device as a supplement to human memory, a second brain so to speak.

The Memex

All things to be stored and accessed via the Memex are first photographed and stored in the form of microfilm. Each item is indexed and assigned a code. They can then be accessed by the user by typing in the code on the keyboard. All this is merely a forward projection of present-day technology Vannevar knew of; but his unique contribution to this was the idea of “tying” two items together.

The user can build a “trail” by joining together two items. At the bottom of each item are a number of blank code spaces, and whenever items are tied together the same code appears on both of them. Thereafter, at any time, when one of these items is in view, the other can be instantly recalled merely by tapping a button below the corresponding code space.

Vannevar Bush envisioned a world where encyclopaedias would encode the expertise and experiences of people in addition to storing information. A web of trails strung across oceans of textual information, joining together related information in an intelligent fashion.

The Memex lacked a true hypertext system, seeing as only entire pages could be linked with each other and not parts of pages themselves. However, his work inspired the two American men generally credited with the invention of hypertext, Ted Nelson and Douglas Engelbart.

The Memex in action:

Hypertext

In a Vassar College Miscellany News article dated February 3, 1965, "Professor Nelson Talk Analyzes P.R.I.D.E.," written by Laurie Wedeles, Nelson is quoted as having used the word "hyper-text” for the first time in history.

Theodor Nelson , who coined the term hypertext, acknowledges his debt to Bush but explains differences between the technologies : "In Bush's trails, the user had no choices to make as he moved through the sequence of items, except at an intersection of trails . With computer storage, however, no sequence need be imposed on the material ; and, instead of storing materials in their order of arrival or of being noticed, it will be possible to create overall structures of greater useful complexity"

From Paterson, Memex, and Hypertext by T. Hugh Crawford

Nelson took Bush’s ideas forward, thinking of hypertext in terms of being implemented inside a digital computer rather than an analog one.

Project Xanadu

In Xanadu did Kubla Khan A stately pleasure-dome decree: Where Alph, the sacred river, ran Through caverns measureless to man Down to a sunless sea. - Samuel Coleridge

In 1960, Nelson founded the world’s first hypertext project, Xanadu. The first attempt at an implementation of this was started as early as 1960, but it wasn’t until 1988 that anything even remotely close to what was promised was released. This lead to Wired magazine publishing an article called "The Curse of Xanadu", calling Project Xanadu "the longest-running vaporware story in the history of the computer industry". A version described as "a working deliverable", OpenXanadu, was made available in 2014.

You can view Nelson’s vision for Xanadu by clicking the link named OpenXanadu. It looks something like this:

As far as I could understand, Xanadu links are necessarily two way - when a document is linked to another, both documents will reference each other. Once a “xanadoc” is published, it’s immutable: you cannot change it. Also, it cannot contain any new contents, “since we believe all media elements should be permanized and addressable.”

Currently, Project Xanadu has a prototype viewer and a sample “xanadoc”. No editor has been made available as of now.

From Xanadu’s official website

This ended up being longer and taking more time than anticipated. When I began this expedition into the thickets of what is essentially modern historiography, I did so unaware that hypertext had such a long, rich and nuanced history. This is why I am splitting this up into multiple parts. Part II will cover Douglas Engelbart’s and Andries van Dam’s parts in the story, part III will look at further pre-Internet hypertext projects (most notably Apple's hypercard), the modern web and the future.